TL-B Types

This information is very low-level and could be hard to understand for newcomers. So feel free to read about it later.

In this section, complex and unconventional typed language binary (TL-B) structures are analyzed. To get started, we recommend reading this documentation first to become more familiar with the topic.

Either

left$0 {X:Type} {Y:Type} value:X = Either X Y;

right$1 {X:Type} {Y:Type} value:Y = Either X Y;

The Either type is used when one of two resulting types are possible. In this case, the type choice depends on the prefix bit shown. If the prefix bit is 0, the left type is serialized, while if the 1 prefix bit is used, the right one is serialized.

It is used, for example, when serializing messages, when the body is either part of the main cell or linked to another cell.

Maybe

nothing$0 {X:Type} = Maybe X;

just$1 {X:Type} value:X = Maybe X;

The Maybe type is used in conjunction with optional values. In these instances, if the first bit is 0, the value itself is not serialized (and is actually skipped), while if the value is 1, it is serialized.

Both

pair$_ {X:Type} {Y:Type} first:X second:Y = Both X Y;

The Both type variation is used only in conjunction with normal pairs, whereby both types are serialized, one after the other, without conditions.

Unary

The Unary functional type is commonly used for dynamic sizing in structures such as hml_short.

Unary presents two main options:

unary_zero$0 = Unary ~0;

unary_succ$1 {n:#} x:(Unary ~n) = Unary ~(n + 1);

Unary serialization

Generally, using the unary_zero variation is quite simple: if the first bit is 0, then the result of whole Unary deserialization is 0.

That said, the unary_succ variation is more complex because it is loaded recursively and possesses a value of ~(n + 1). This means it sequentially calls itself until it reaches unary_zero. In other words, the desired value will be equal to the number of units in a row.

For instance, let's analyze serialization of the bitstring 110.

The call chain will be as follows:

unary_succ$1 -> unary_succ$1 -> unary_zero$0

Once we reach unary_zero, the value is returned to the end of a serialized bitstring similarly to a recursive function call.

Now, to understand the result more clearly, let's retrieve the return value path, which is displayed as follows:

0 -> ~(0 + 1) -> ~(1 + 1) -> 2, that means we serialized 110 in Unary 2.

Unary deserialization

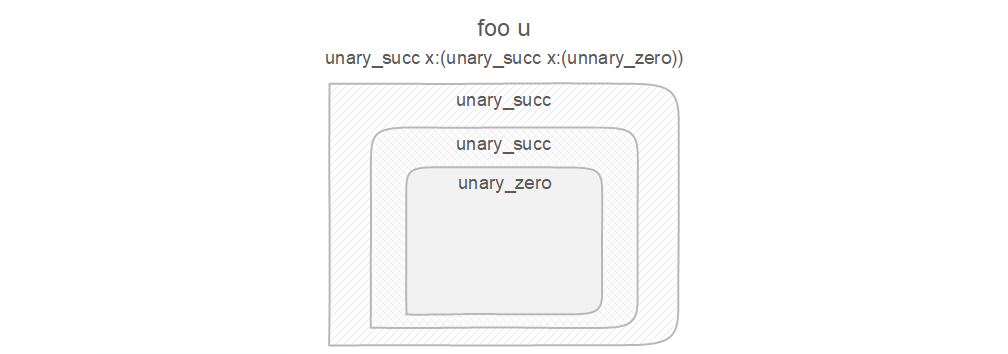

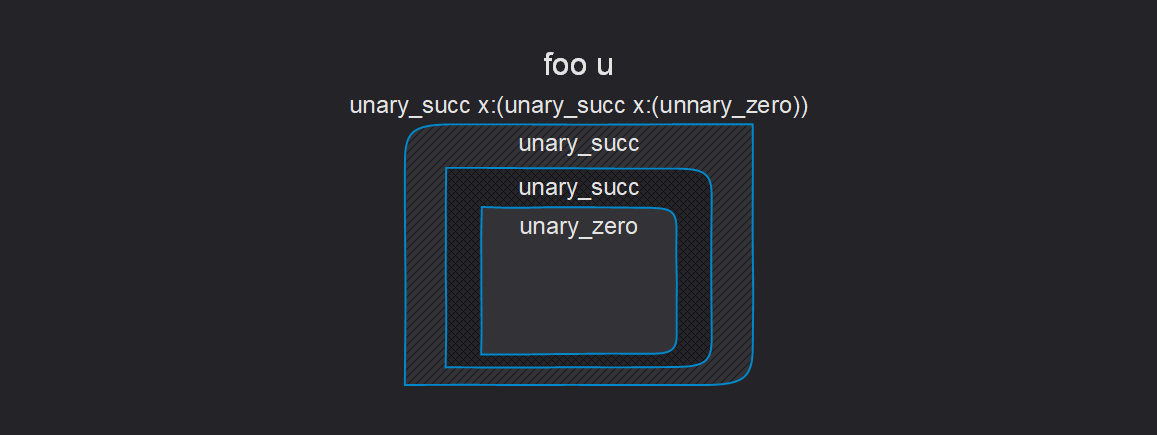

Suppose we have Foo type:

foo$_ u:(Unary 2) = Foo;

According said above, Foo will be deserialized into:

foo u:(unary_succ x:(unary_succ x:(unnary_zero)))

Hashmap

The Hashmap complex type is used for storing dict from the FunC smart contract code(dict).

The following TL-B structures are used to serialize a Hashmap with a fixed key length:

hm_edge#_ {n:#} {X:Type} {l:#} {m:#} label:(HmLabel ~l n)

{n = (~m) + l} node:(HashmapNode m X) = Hashmap n X;

hmn_leaf#_ {X:Type} value:X = HashmapNode 0 X;

hmn_fork#_ {n:#} {X:Type} left:^(Hashmap n X)

right:^(Hashmap n X) = HashmapNode (n + 1) X;

hml_short$0 {m:#} {n:#} len:(Unary ~n) {n <= m} s:(n * Bit) = HmLabel ~n m;

hml_long$10 {m:#} n:(#<= m) s:(n * Bit) = HmLabel ~n m;

hml_same$11 {m:#} v:Bit n:(#<= m) = HmLabel ~n m;

unary_zero$0 = Unary ~0;

unary_succ$1 {n:#} x:(Unary ~n) = Unary ~(n + 1);

hme_empty$0 {n:#} {X:Type} = HashmapE n X;

hme_root$1 {n:#} {X:Type} root:^(Hashmap n X) = HashmapE n X;

This means the root structure uses HashmapE and either of its two states: including hme_empty or hme_root.

Hashmap parsing example

As an example, consider the following Cell, given in binary form.

1[1] -> {

2[00] -> {

7[1001000] -> {

25[1010000010000001100001001],

25[1010000010000000001101111]

},

28[1011100000000000001100001001]

}

}

This Cell makes use of the HashmapE structure type and possesses an 8-bit key size and its values make use of the uint16 number framework (HashmapE 8 uint16). HashmapE makes use of distinct 3 key types:

1 = 777

17 = 111

128 = 777

To parse this Hashmap, we need to know in advance which structure type to use, either hme_empty or hme_root. This is determined by identifying the correct prefix. The hme empty variation uses one bit 0 (hme_empty$0), while hme root uses one bit 1 (hme_root$1). After reading the first bit, it is determined that it is equal to one (1[1]), meaning it is the hme_root variation.

Now, let's fill out the structure variables with known values, with the initial result being:

hme_root$1 {n:#} {X:Type} root:^(Hashmap 8 uint16) = HashmapE 8 uint16;

Here the one bit prefix is already read, yet within the {} denotes conditions that don’t need to be read. The condition {n:#} means that n is any uint32 number, while {X:Type} means that X can employ any type.

The next portion that needs to be read is the root:^(Hashmap 8 uint16), while the ^ symbol denotes a link that must be loaded.

2[00] -> {

7[1001000] -> {

25[1010000010000001100001001],

25[1010000010000000001101111]

},

28[1011100000000000001100001001]

}

Initiating Branch Parsing

According to our schema, this is the correct Hashmap 8 uint16 structure. Next, we fill it with known values and obtain a result of:

hm_edge#_ {n:#} {X:Type} {l:#} {m:#} label:(HmLabel ~l 8)

{8 = (~m) + l} node:(HashmapNode m uint16) = Hashmap 8 uint16;

As is shown above, conditional variables {l:#} and {m:#} have now appeared, yet the values of both variables are unknown to us. Also, after reading the corresponding label, it's clear that n is involved in the equation {n = (~m) + l}, in this case we calculate l and m, the sign tells us the resulting value of ~.

To determine the value of l, we must load the label:(HmLabel ~l uint16) sequence. As is shown below, the HmLabel has 3 basic structural options:

hml_short$0 {m:#} {n:#} len:(Unary ~n) {n <= m} s:(n * Bit) = HmLabel ~n m;

hml_long$10 {m:#} n:(#<= m) s:(n * Bit) = HmLabel ~n m;

hml_same$11 {m:#} v:Bit n:(#<= m) = HmLabel ~n m;

Each option is determined by the corresponding prefix. Currently, our root cell is made up of 2 zero bits, which is displayed as: (2[00]). Therefore, the only logical option is hml_short$0, which makes use of a prefix beginning with 0.

Fill hml_short with known values:

hml_short$0 {m:#} {n:#} len:(Unary ~n) {n <= 8} s:(n * Bit) = HmLabel ~n 8

In this case, we don't know the value of n, but since it has a ~ character, it’s possible to calculate it. To accomplish this, we load len:(Unary ~n), more about Unary here.

In this case, we started with 2[00], yet after defining the type HmLabel, only one of the two bits still exists.

Therefore, we load it and see that its value is 0, which means it clearly uses the unary_zero$0 variation. That means that the n value using the HmLabel variation is zero.

Next, it is necessary to complete the hml_short variation sequence using the calculated n value:

hml_short$0 {m:#} {n:#} len:0 {n <= 8} s:(0 * Bit) = HmLabel 0 8

It turns out we have an empty HmLabel denoted as, s = 0, therefore there is nothing to download.

Next, we supplement our structure with the calculated value of l as follows:

hm_edge#_ {n:#} {X:Type} {l:0} {m:#} label:(HmLabel 0 8)

{8 = (~m) + 0} node:(HashmapNode m uint16) = Hashmap 8 uint16;

Now that we have calculated the value of l, we can also calculate m using the equation n = (~m) + 0, i.e. m = n - 0, m = n = 8.

After determining all unknown values it is now possible to load the node:(HashmapNode 8 uint16).

As far as the HashmapNode goes, we have options:

hmn_leaf#_ {X:Type} value:X = HashmapNode 0 X;

hmn_fork#_ {n:#} {X:Type} left:^(Hashmap n X)

right:^(Hashmap n X) = HashmapNode (n + 1) X;

In this case, we determine the option not by using the prefix, but by using the parameter. This means that if n = 0, then the correct end result will be either hmn_leaf or hmn_fork.

In this example, the result is n = 8 (the hmn_fork variation). We make use of the hmn_fork variation and fill in the known values:

hmn_fork#_ {n:#} {X:uint16} left:^(Hashmap n uint16)

right:^(Hashmap n uint16) = HashmapNode (n + 1) uint16;

After entering the known values, we must calculate the HashmapNode (n + 1) uint16. This means that the resulting value of n must be equal to our parameter, i.e. 8.

To calculate the local value of n, we need to calculate it using the following formula: n = (n_local + 1) -> n_local = (n - 1) -> n_local = (8 - 1) -> n_local = 7.

hmn_fork#_ {n:#} {X:uint16} left:^(Hashmap 7 uint16)

right:^(Hashmap 7 uint16) = HashmapNode (7 + 1) uint16;

Now that we know the above formula is required, obtaining the end result is simple. Next we load the left and right branches and for each subsequent branch the process is repeated.

Analyzing Loaded Hashmap Values

Continuing with the previous example, let’s examine how the process of loading branches works (for dict values)., i.e. 28[1011100000000000001100001001]

The end result becomes hm_edge yet again and the next step is to fill the sequence with the correct known values as follows:

hm_edge#_ {n:#} {X:Type} {l:#} {m:#} label:(HmLabel ~l 7)

{7 = (~m) + l} node:(HashmapNode m uint16) = Hashmap 7 uint16;

Next the HmLabel response is loaded using the HmLabel variation because the prefix is 10.

hml_long$10 {m:#} n:(#<= m) s:(n * Bit) = HmLabel ~n m;

Now, let's fill in the sequence:

hml_long$10 {m:#} n:(#<= 7) s:(n * Bit) = HmLabel ~n 7;

The new construction - n:(#<= 7), clearly denotes a sizing value that corresponds to the number 7, which is in fact a log2 from the number + 1. But for simplicity, we could count the number of bits needed to write the number 7.

Relatedly, the number 7 in binary form is 111; therefore 3 bits are required, meaning the value for n = 3.

hml_long$10 {m:#} n:(## 3) s:(n * Bit) = HmLabel ~n 7;

Next we load n into the sequence, with an end result of 111, which as we noted above = 7 coincidentally. Next, we load s into the sequence, 7 bits - 0000000. Remember, s is part of the key.

Next we return to the top of the sequence and fill in the resulting l:

hm_edge#_ {n:#} {X:Type} {l:#} {m:#} label:(HmLabel 7 7)

{7 = (~m) + 7} node:(HashmapNode m uint16) = Hashmap 7 uint16;

Then we calculate the value of m, m = 7 - 7, therefore the value of m = 0.

Since the value of m = 0, the structure is perfect for use with a HashmapNode:

hmn_leaf#_ {X:Type} value:X = HashmapNode 0 X;

Next we substitute our uint16 type and load the value. The remaining 16 bits of 0000001100001001 in decimal form is 777, therefore our value.

Now let's restore the key, we must combine the ordered list of all parts of the key that were computed previously. Each of the two related key parts unite with one bit based on which type branches are used. For the right branch, ‘1’ bit is added, and for the left branch ‘0’ bit is added. If a full HmLabel exists above, then its bits are added to the key.

In this case specifically, 7 bits are taken from the HmLabel 0000000 and ‘1’ bit is added before the sequence of zeros because the value was obtained from the right branch. The end result is 8 bits in total or 10000000, meaning the key value equals 128.

Other Hashmap Types

Now that we have discussed Hashmaps and how to load the standardized Hashmap type, let’s explain how the additional Hashmap types work.

HashmapAugE

ahm_edge#_ {n:#} {X:Type} {Y:Type} {l:#} {m:#}

label:(HmLabel ~l n) {n = (~m) + l}

node:(HashmapAugNode m X Y) = HashmapAug n X Y;

ahmn_leaf#_ {X:Type} {Y:Type} extra:Y value:X = HashmapAugNode 0 X Y;

ahmn_fork#_ {n:#} {X:Type} {Y:Type} left:^(HashmapAug n X Y)

right:^(HashmapAug n X Y) extra:Y = HashmapAugNode (n + 1) X Y;

ahme_empty$0 {n:#} {X:Type} {Y:Type} extra:Y

= HashmapAugE n X Y;

ahme_root$1 {n:#} {X:Type} {Y:Type} root:^(HashmapAug n X Y)

extra:Y = HashmapAugE n X Y;

The main difference between the HashmapAugE and the regular Hashmap is the presence of an extra:Y field in each node (not just in leafs with values).

PfxHashmap

phm_edge#_ {n:#} {X:Type} {l:#} {m:#} label:(HmLabel ~l n)

{n = (~m) + l} node:(PfxHashmapNode m X)

= PfxHashmap n X;

phmn_leaf$0 {n:#} {X:Type} value:X = PfxHashmapNode n X;

phmn_fork$1 {n:#} {X:Type} left:^(PfxHashmap n X)

right:^(PfxHashmap n X) = PfxHashmapNode (n + 1) X;

phme_empty$0 {n:#} {X:Type} = PfxHashmapE n X;

phme_root$1 {n:#} {X:Type} root:^(PfxHashmap n X)

= PfxHashmapE n X;

The main difference between the PfxHashmap and the regular Hashmap is its ability to store different key lengths due to the presence of the phmn_leaf$0 and phmn_fork$1 nodes.

VarHashmap

vhm_edge#_ {n:#} {X:Type} {l:#} {m:#} label:(HmLabel ~l n)

{n = (~m) + l} node:(VarHashmapNode m X)

= VarHashmap n X;

vhmn_leaf$00 {n:#} {X:Type} value:X = VarHashmapNode n X;

vhmn_fork$01 {n:#} {X:Type} left:^(VarHashmap n X)

right:^(VarHashmap n X) value:(Maybe X)

= VarHashmapNode (n + 1) X;

vhmn_cont$1 {n:#} {X:Type} branch:Bit child:^(VarHashmap n X)

value:X = VarHashmapNode (n + 1) X;

// nothing$0 {X:Type} = Maybe X;

// just$1 {X:Type} value:X = Maybe X;

vhme_empty$0 {n:#} {X:Type} = VarHashmapE n X;

vhme_root$1 {n:#} {X:Type} root:^(VarHashmap n X)

= VarHashmapE n X;

The main difference between the VarHashmap and the regular Hashmap is its ability to store different key lengths due to the presence of the vhmn_leaf$00 and vhmn_fork$01 nodes. Additionally, the VarHashmap is able to form a common value prefix (child map) at the expense of the vhmn_cont$1.

BinTree

bta_leaf$0 {X:Type} {Y:Type} extra:Y leaf:X = BinTreeAug X Y;

bta_fork$1 {X:Type} {Y:Type} left:^(BinTreeAug X Y)

right:^(BinTreeAug X Y) extra:Y = BinTreeAug X Y;

The binary tree key generation mechanism works in a similar manner to the standardized Hashmap framework but doesn't use labels and only includes branch prefixes.

Addresses

TON addresses are formed with the sha256 hashing mechanism using the TL-B StateInit structure. This means that the address can be calculated prior to network contract deployment.

Serialization

Standard addresses such as EQBL2_3lMiyywU17g-or8N7v9hDmPCpttzBPE2isF2GTzpK4 use the base64 uri for byte encoding.

Typically, they have a length of 36 bytes, the last 2 of which are the crc16 checksum calculated with XMODEM table, while the first byte represents the flag, with the second representing the workchain.

The 32 bytes in the middle are the data of the address itself (also calls AccountID), often represented in schemas such as int256.

References

Here a link to the original article by Oleg Baranov.